Katharine Quarmby investigates the death of Danny Tozer and its aftermath on his family

Click here for a Plain English Summary

On 22 September 2015 Danny Tozer died in hospital at the age of 36. An unexpected death, of a healthy young man. He left behind a loving family, who had expected him to live much longer. He was a son, brother, uncle and friend.

Danny had been earlier diagnosed with autism, a learning disability and epilepsy but the family had been told when he was just three that he would have a typical life expectancy. But at his inquest the coroner decided that he had died of natural causes; nobody could have prevented it. Danny’s death was a tragedy, but it could not be avoided – such is the underlying message of such a determination.

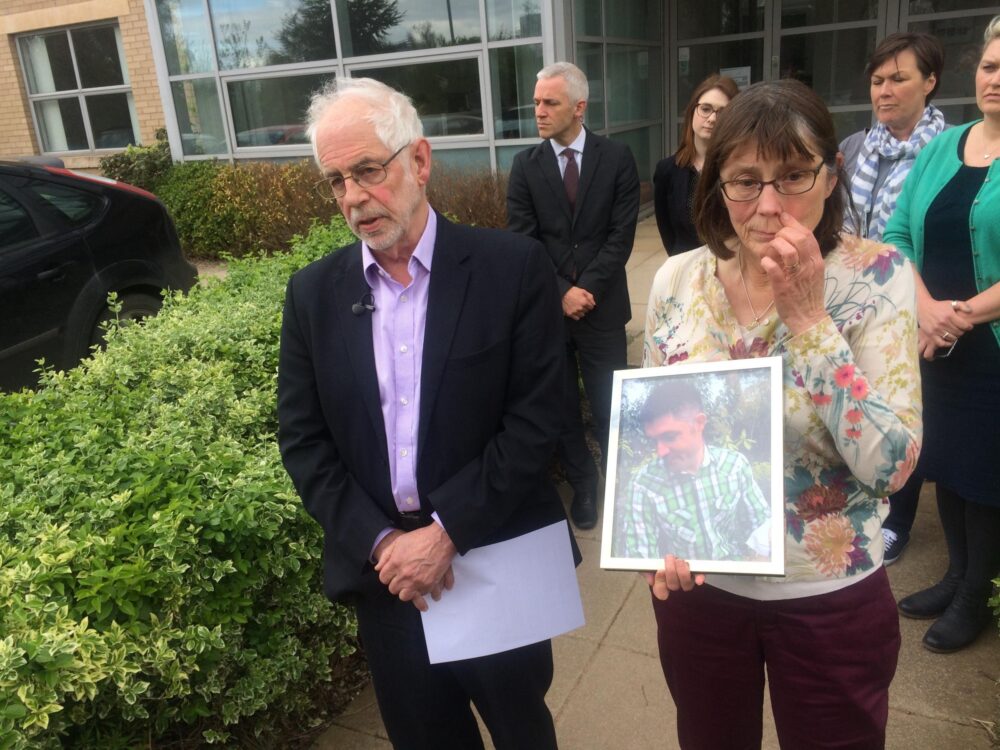

It was indeed a tragedy, but the question of whether Danny’s death could have been prevented has haunted Danny’s parents, Rosie and Tim Tozer, ever since. As they said in a statement at the time of the inquest, in April 2018: “Danny’s senseless death has devastated his family and friends”. It deprived them of the opportunity to spend a life with someone who, as they put it, “lit up our lives”.

This investigation pieces together what happened to Danny before he died and it looks at the system after an unexpected death. The Tozers have fought long and hard to make sense of the events leading up to Danny’s death. They also have questions about the mechanisms for transparency that creak into services after deaths that may be unexpected or even preventable. The Tozers remain fearful of what could happen to others cared for in the current system.

Without understanding the coronial service, the lack of sanctions in the social care system, the lack of heft behind so many similar investigations carried out – and the feeling that so many shrug off the early deaths of disabled people – we cannot make sense of what happened to Danny. His death may have been a tragedy, but it also serves as a warning that the system that should care and support for people with disabilities is failing and that answers about that failure are few and far between. Tragedies hold nobody accountable. The Tozers – and many other families who have lost members in similar circumstances – feel that transparency and accountability after the death of a loved family member with a disability are lacking, to say the least.

Danny’s case is one of a number of deaths of people with learning disabilities who died young. The Learning Disability Mortality Review Programme, which provides information about the deaths of people with learning disabilities, found that people with learning disabilities had around a 25 year shorter life expectancy than the general population. Around 42% of deaths of people with learning disabilities are considered to be premature. Likewise, the charity Autistica has found that only half of people with autism, learning disabilities and epilepsy reach the age of 40.

Families bereaved early, who believe that the deaths of their loved ones happened in preventable circumstances, include Connor Sparrowhawk, Oliver McGowan, Joanne Wadsworth, Richard Handley. All were described at various times as having complex needs. But that is no excuse for poor care, what often appears to be a lack of timely support and missed opportunities. There is often a pattern of neglect or missed opportunities that seems to run up to their deaths. The loss is one thing; the pattern of deaths and what looks like a systems failure is another.

Speaking to Rosie and Tim now, in their bright home near York over Zoom calls to discuss what happened to Danny, I glimpse a picture of what might have been – and what is. Life continues after an early bereavement but the photo frames of happy family occasions take on an extra poignancy, a glimpse of a past that was cut off, has lost its link to now and to the future.

About Danny

Danny, the oldest of three children, was born in 1979. He was, according to his mother, Rosie, “a cheery and sociable toddler” who was speaking from about two years onwards. Danny started to lose his speech and to become more anxious about a year later, around the time his sister, Rowena was born.

When Danny was three and a half he was diagnosed as autistic and he started to sign and learn at a unit specialising in autism when he was six. A year earlier Danny’s brother Sam was born. Sam developed epilepsy from about 18 months old, could never speak and required total physical care. Rosie remembers: “Danny was gentle with Sam and often stroked and cuddled him.”

Rowena remembers her childhood as idyllic and the siblings all developed a strong bond. “Having two disabled siblings was my normal, we were always together, we didn’t have family nearby so we went out a lot and we were very close.”

She adds that life was chaotic, but fun. “Danny and I liked the same things, the same music, we liked walking together and Sam was always there too.”

At age 19, after a mixed experience at weekly boarding school, Danny moved to live in an established autistic community, set up by parents, in the Wirral. It was a peaceful place to live with people of his own age, the Tozers enjoyed visiting him and he came home around once a month.

When Danny was 24 Sam became seriously ill and died from pneumonia and Danny came to say goodbye to him in a local hospice. Shortly after that bereavement, Danny had his first seizure, and later a pattern of about one a month emerged. As long as Danny was kept safe during the seizure it resolved itself in a few minutes.

Rowena saw Danny when she could, but was studying and then working in London, before moving to New York in 2010 for work. Over time things got more difficult in the Wirral home, with limited one to one support and with difficulties presenting themselves regarding other clients, some of whom were violent. Danny was attacked at least once a month and the Tozers wanted him to be in a smaller and safer home. Another placement in Liverpool was successful for a while, but the Tozers, who by then were in their mid-sixties, wanted to be closer to him and enjoy time with him. Danny was fun to be around.

His mum Rosie remembers how Danny loved observing the social whirl, wherever it was. “He liked a cup of tea for the social attention, he was really a builder’s tea person. He loved the ritual of it all, the teapot, the cups – he loved cups of any description. And beer, he loved drinking beer as well.”

Moving into the Mencap home

The City of York Council (CYC), which commissioned Danny’s care package with some particular continuing health funding, identified a supported living home in York as the only possible placement. The house, which was a large bungalow for six residents, was run by Mencap York Domiciliary Care. The charity, Royal Mencap, bills itself as “the leading voice of learning disability” and the Tozers felt that Danny could not only be closer to them, but should be in safe hands.

They spent a considerable amount of time trying to plan Danny’s new placement and arranging his move. They wanted to make the best of the change for him and spent a lot of time trying to engage with and help staff. At first, they thought things were promising, although they worried that Mencap locally might need to change its approach to support an active person like Danny who was used to a range of activities. One benefit was that Danny could come out with them in the city more and go on other excursions.

Tim remembers how much Danny liked a day out:

“If we were walking through a town centre he would suddenly elbow me and then I’d see, it was a café or pub and he just liked the social occasion of being in one. He liked to sit at the bar and observe the people around. When I was more involved with students he’d sometimes tag along, be one of the crowd. He would sit down with a bunch of students and if someone didn’t finish their beer he’d just pick it up. He was so happy.”

Concerns about care

However, despite happy family outings, they were soon worried about the care offered, which they felt was often lacking with inadequate staffing for tenants and confused and inconsistent support; that leadership was poor and that monitoring and co-ordination were largely absent.

Best practice with people with autism recommends a small team of motivated staff. Although the Tozers felt that the manager had tried to find suitable staff to support Danny at the start, they were often unsupervised and poorly supported, and not all staff were up to speed with Danny’s communication support and his epilepsy. Danny had to be accompanied at all times when outside and his family was told that he would be subject to frequent checks for seizures associated with his epilepsy.

The home at that time had five or six tenants and many staff members, with a lot of turnover. Whilst Rosie says that there were some motivated staff, some others, she felt, appeared to have no little or understanding of Danny’s support needs. “They could not work to support him in an appropriate way and were not motivated to learn, having a view that they already knew best. After 36 years we still felt we were learning new things from Danny every time we were with him…It was hard to know how to communicate our worries and which to prioritise.”

Tim says:

“it became clear that many staff at Maple Avenue were not used to or comfortable with providing support for activities and the ethos of the house did feel rather like an old people’s home or a nursing home.”

The Tozers did their best to devise activities which Danny liked, such as horse riding, running and trampolining but found themselves in constant negotiations to make them happen.

When they visited they noted that a large TV was often left on, blaring out loud, there were few activities, many staff members did not want to engage with them and suggestions from them often ignored. On one occasion Rosie says a member of staff told her to stop fussing – something that has not been denied by Mencap.

The Tozers requested to see Danny’s activity log so that they could contribute to this when he was with them but this was refused due to respect for his privacy. Emails and phone calls were not always answered and some staff seemed even to be hostile. Although staff did start a diary that the Tozers could see, it was not filled in in any great detail.

The Tozers felt that Danny’s personal grooming was poor, and it took two years before staff cut his fingernails for him or provided soap in the bathroom. He sometimes smelt or was poorly groomed. At one time the key worker system was removed, without parents being informed but later introduced. In 2014 Danny started to become agitated, and there were three episodes of self harm, following on from an unsettled period in the home.

On the first year that Danny arrived in the home, the Tozers took Danny out for the day on his birthday and had left balloons at the home. They were left in a bunch on the bed and it became clear that there was no intention to celebrate his birthday with others in the house, with staff explaining that policy was no exchange of presents for birthdays or Christmas.

The Tozers asked whether the new GP that Danny was registered with would be referring him to an epilepsy specialist. This was agreed only after the Tozers pushed for it. Things continued to be up and down at the home, better when friendly staff members were there, but never entirely stable. On one occasion in 2014 the family found that Danny’s bedroom windows had been whited out so he could not see out. The explanation was that children were visiting next door and if they were jumping on their trampoline they might see Danny change. Rosie rang the Mencap national helpline, which raised human rights concerns.

In April 2015 Rowena brought her daughter back to the UK and the Tozer family was reunited. Danny was delighted to meet his new niece. But Rowena remembers that there was constant “stress and challenge” for her parents, as they were so concerned about the place where he was living.

In particular, the Tozers were anxious about the lack of safety around managing Danny’s epilepsy, as his seizures had increased slightly in frequency over the years. The Tozers had raised concerns about the management of Danny’s epilepsy and about the hard floors in some parts of the bungalow. A care treatment booklet was created and reviewed in June 2015. Danny’s bed was fitted with a seizure sensor mat and the Tozers were told Danny would be checked on every five minutes if out of sight.

In early August 2015 Danny successfully ran the York 10K and family pictures show a healthy and beaming young man. A few days later he went into hospital for a dental check up and the dentists found that three teeth had to be removed under general anaesthetic as they were rotten. This would have taken one to two years to develop and the Tozer’s fears that staff were not helping with dental hygiene were realised.

The next day, Danny’s 36th birthday, the Tozers took him to Scarborough for the day. At a meeting on August 27th the care manager confirmed that if Danny didn’t have a dental care plan that could be construed as neglect. At that meeting with some staff the Tozers also raised Danny being left behind closed doors such as when in the toilet without staff nearby and gathered that his bedroom door was shut in the mornings because a female tenant might walk past. The Tozers were not reassured by staff responses about his safety.

Danny’s death

On the late August Bank Holiday in 2015, Danny came home and the family went to Sleights for the weekend. This was the last time they saw him conscious. Rosie remembers: “On the Sunday night Danny danced on the beach with the waves in the dark, chuckling.” But he seemed quiet and distant on the way back and they noticed that he was more anxious and was starting to make a guttural clicking noise, which seemed to be an attempt to self calm. By that point they had resolved that they would try and move Danny to a different placement. They would make a joint family decision about where that should be when their daughter, Rowena, returned from working outside the UK in November 2015.

Tim and Rosie were away overnight in Oxford in the autumn of 2015 when they received a call. It was the 21st of September. They were told that Danny had suffered a cardiac arrest. They rushed back to York. “We thought perhaps he had a seizure. We got back to hospital and found him in intensive care. By then his heart had been restarted twice.” Rosie and Tim never saw him regain consciousness. Rowena, her husband and baby had flown back from New York but arrived just before the doctors confirmed that Danny was now brain dead.

Bit by bit the Tozers have pieced together a patchy picture of what happened that day as they rushed back from Oxford. Danny had been left alone, awake, in his bedroom, for up to 35 minutes. His support plan stated that he should be checked every five to ten minutes and an ambulance called if a seizure lasted more than five minutes. He was found unresponsive in his room at just before 9am. An ambulance was called, and the records show that he was found face down and grey in the bed.

Danny’s heart was restarted by paramedics and he was rushed to hospital, sedated and put on life support. He died at 6pm the following evening, surrounded by his family.

The family asked that Danny be considered for organ donation ( something that had not been possible for Sam, his brother, when he died), but told if they did so that no post-mortem would be carried out. Rosie says: “We understood that a post-mortem would not provide further useful evidence, but the coroner asked the consultant if we thought there was foul play; we responded that we did not think that he had been deliberately killed but we felt that he might have been neglected the previous morning.” His organs were then donated to help five people – a huge comfort to the Tozers. Dr Yates, the intensive care consultant, later filed a statement to the coroner, in which he stated: “It was felt by all treating clinicians that Daniel’s cardiac arrest was most likely related to a hypoxic event secondary to a prolonged seizure”.

Danny’s funeral took place on a week or so later.

Rosie remembers that it was a warm and sunny autumn day. The village where they live turned out and the hall was used for tea, which Danny had always loved going to. The bells were rung at the church; church bells delighted Danny.

“Tim played the organ, including Danny Boy, and there were a few short poems read by family members and then a friend played the Ashokan Farewell on his violin as the coffin was taken to the churchyard where he was buried next to Sam. The hymn, Simple Gifts, was played, and other songs which we had also played at Sam’s funeral. Sam has a small stone frog on his grave and as the coffin was lowered into the ground a tiny frog jumped onto it – lots of people said that was Sam greeting his brother. I can’t remember much afterwards but we all had fish and chips from the Wednesday van as relatives stayed overnight. We were still in a trance and just wishing he was there.”

Two months later the family held a slighter bigger celebration the same place, and people came from further afield, including from the Wirral Autistic Society. Danny’s riding instructor, music tutor and athletics coach came with lovely memories of Danny, says Rosie. “Everyone was invited to share their memories. We showed video and had Danny style food – olives, Twiglets and Monster Munch. Then we let off red balloons and cheered.”

To lose a well loved child is one thing. But the second, common to so many parents with disabled children who are bereaved is that the aftermath is re-traumatising. So many deaths are put down to natural causes, allowing poor care to escape scrutiny. The Tozers were determined that Danny’s death should not go unnoticed. So, like other parents who have lost their disabled children, they became campaigners for truth, accountability and positive changes in support to protect others with similar disabilities. Justice.

PART 2 – THE INVESTIGATION

Despite the overwhelming shock and grief, the Tozers, even at this early stage, took some legal advice, which recommended that they write to the coroner to request that an inquest was open and adjourned, pending an independent investigation. The Care Quality Commission (CQC), which monitors and inspects all health and social care services in England, advised that the Tozers should write letters of complaint to City of York Council (CYC) and Mencap. The Coroner replied that initial inquiries did not suggest malpractice and that he was not obliged to hold an inquest as Danny was not under a Deprivation of Liberty Safeguard (DOLS). (Legally, as the Tozers understand it, he should have been, but his case, like others, was snarled in a backlog.)

In the following months, whilst still grieving their son, the Tozers anticipated that, in line with the Care Act 2014, the local council would instigate an independent Adult Safeguarding Review. However, the council did not do so, despite Danny’s death seeming to fit the criteria for carrying out a so-called Section 44 review. Instead, an initial safeguarding inquiry was closed down within a week, without the family’s involvement or knowledge.

The charity, Inquest, which provides support on state related deaths and their investigation to bereaved people, confirmed in a phone call with one of its case workers that the Tozers had a case for an inquest, but needed a solicitor who had not worked for Mencap. In January 2016, Gemma Vine, a solicitor in Leeds, took on the case. The local MP, Julian Sturdy, also wrote to the Coroner supporting the inquest and saying that the family “had a right to expect good quality care for Danny.”

In April 2016, Janine Tregelles, at that time the Chief Executive Officer of Mencap, came to see the Tozers with the head of her legal team. The Tozers say that she was critical of the situation in the house, which she called “toxic”. These observations were put to Mencap, and not denied. Its statement can be found at the end of the article. She promised that Mencap would be transparent during the external review and expressed sorrow at Danny’s death.

The home where Danny lived and other supported living homes in York run by Mencap – 12 locations supporting over 40 adults – were inspected by the CQC shortly after Danny’s death. The CQC released a report in early 2016, noting that the facility needed improvement in five areas and finding that the service was found to “Requires Improvement” with four breaches of regulations, including one of risk management. These included the safety, effectiveness, caring, responsiveness and leadership within its service. The Inspector had visited the Tozers regarding the inspection, but told them that as Danny was no longer resident, evidence about his care could not be included in the report. Tregelles said of the report, in a letter to the family, that it was based on “some factual inaccuracies” although she did acknowledge that Mencap needed to improve its engagement with families. (Since then, CQC visits to the service confirm that it has improved.)

In December that year the CQC concluded, after an investigation lasting from January-September 2016, that the body would not prosecute Mencap for health and safety breaches. The CQC had talked to Mencap and the Coroner’s office and had decided that as it was not known whether Danny had his seizure within the 30 minutes he was left, he might not have survived if found sooner. The campaigner for open justice, George Julian, who live tweets inquests, tribunals and other hearings to amplify scrutiny and to hold systems to account, supported the family to complain to the CQC about the lack of family involvement in the investigation.

In the same month Rosie Tozer met Mary Ann Bruce, who led the so-called 2015 Mazars review of deaths at Southern Health mental health and learning disability facilities, at a Sheffield conference. In Bruce’s presentation she argued that all the individual points in care can seem like minor incidents – such as lack of teeth brushing, or someone becoming obese because of medication – but that together they form a pattern that can highlight why a tragedy occurs. Family members have an overview, which helps put that jigsaw together. Bruce told Rosie Tozer that she saw parallels between the cases she had investigated for Southern Health and Danny’s case.

Critical review

After the Tozers made official complaints to CYC and Mencap on the advice of the CQC, the council commissioned an independent management review, a largely paper exercise which nonetheless roundly criticised both CYC and Mencap and raised major concerns when it reported in early 2017. York Council’s then Assistant Director of Adult Social Care, Michael Melvin, shared the review with the Tozer family and said: “On behalf of the council…we want to offer you our sincere apologies. The review clearly highlights very significant shortcomings in how we approached supporting Danny and in particular how we involved yourselves as his parents and the most significant people in his life.” The council also produced an action plan so that they could improve “how we work with other families in similar situations.”

The review was critical of the treatment that Danny – and the Tozer family – had received. It stated that there was little evidence of a person centred approach or that Danny’s care was centred around his needs, there was no apology to Rosie Tozer when she was told to “stop fussing” by one member of staff and the reviewer found that the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and its Code of Practice were not consistently followed. In particular, the morning routine was not followed on the day that Danny died. There was no record in Danny’s log of ten minute observations, to see if he was ready to get up. The report did identify that there were many support plans in place at the home, including ones for the morning routine and an epilepsy risk assessment, but it stated clearly: “actions on the morning of September 21 were not as agreed in Danny’s support plans,” adding: “Danny was left for longer than he should have been.”

The Tozers wrote back to the council, saying that they welcomed the review, its findings and recommendations but adding: “We believe strongly that the circumstances of Danny’s death should have been the subject of a Section 44 adult safeguarding review. The reviewer never visited the home where Danny died, or spoke to Mencap staff to observe practice and culture.”

Mencap itself had undertaken little or no investigations following Danny’s death, apart from two fact-finding interviews, the review said. The independent review states: “It is therefore difficult to establish, with accuracy and certainty, exactly what happened on the morning of 21 September 2015.” The reviewer found communication between Mencap, York Council and the family to have been “poor after the death of their son and largely instigated by Mr and Mrs Tozer”.

The review concluded that overall Danny’s care was not well planned, was not always centred round his needs and that Danny’s parents did not receive sufficient feedback to alleviate their fears about their son’s support. The review mentioned, again, that staff had failed to safeguard dental health. “Danny’s parents reported feeling distressed by ‘an undercurrent of hostility or irritation on behalf of a few staff’ at [the home]. The analysis of documentation, presented to the reviewer, reinforces and reflects this perception.”

The inquest

In October 2017 the Coroner, agreed to open an inquest. Three Pre Inquest Hearings (PIRs) were held and at the second one, in January 2018, around 20 people representing various agencies were present. Only two people there – Rosie and Tim – had known Danny. It took over two years for the family and thousands of pounds in legal costs to secure an inquest. Legal aid was refused, as is often the case. The Tozer family had fought successfully for an Article 2 inquest, referring to Article 2 of the European Convention of Human Rights. These are enhanced inquests held if a death takes place in state detention and can consider neglect on behalf of an individual or a system. Their legal team also argued for a jury.

Mencap argued successfully to reduce the scope of the inquest to six months before Danny died and for no jury to be present, arguing that a long inquest would be tiring for jurors. Additionally, the charity argued that as Danny wasn’t under a DOLS he could have left hospital freely, adding that Danny didn’t die in the care of Mencap. Danny was unconscious when he was in hospital.

The inquest eventually lasted for seven days, taking place in April 2018. Despite the enhanced powers for such an inquest, Rosie says: “The Coroner seemed to have little experience of an Article 2 Inquest, limiting his brief to the who, where and how of all inquests, which was held without a jury. Rosie Tozer later gave written evidence to Parliament about the inquest. She wrote:

(This info below is taken from the evidence, which you read in full by following the link: https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/10558/pdf/)IS

“The proceedings which were supposed to be investigative rather than adversarial felt stage managed largely by the Mencap barrister, who we felt bullied some witnesses…He also frequently interrupted discussions between us and our barrister, which then made us feel we had not had adequate preparation between witnesses. It seemed like a contest between barristers and the inquest format prevented the truth being established. The Coroner seemed unable or unwilling to prevent a contest between barristers and to lack professional curiosity about the evidence presented.”

Indeed Mencap’s barrister concentrated questioning around whether or not sudden deaths in people with epilepsy should be expected. There was also a focus on Danny masturbating and having private time to do so, this being the reason given why the ten minute checks were not carried out.

Important witnesses were not called, such as the Assistant Director of Adult Social Care, and NHS staff, including one who had written Danny’s epilepsy support plan and another family member who had observed the care at the Mencap house. He was intent on finding ‘natural causes’, and a question was even asked a neurologist whether one could recover from a sudden death in epilepsy.

HM Assistant Coroner Mr Heath concluded that Danny died of natural causes and there was no neglect in his care. He found that the cause of Danny’s death was due to Sudden Unexpected Death in Epilepsy (SUDEP). He commented that the communication between Danny’s family, Mencap, York and the care providers was not satisfactory. His final statement was merely an hour’s summary of what he had heard. It lacked analysis, any identification of failures and ended with a one sentence verdict. Rosie says: “As there were no recommendations from the Coroner the verdict allowed all agencies to abandon any changes they might have made to improve support for people with Danny’s profile who have epilepsy. Though inquest lawyers & social care professionals and campaigners have expressed astonishment and disappointment at the inquest we also feel an opportunity was missed to improve support for others as a meaningful legacy for our son.”

The Coroner did say communication between the family and Mencap and CYC was not satisfactory but that keeping an eye on Danny to ensure his safety would have been too difficult. The Tozers point out that they did exactly that when they had Danny at home.

Sara Ryan’s son, Connor Sparrowhawk (often known as Laughing Boy, or LB), died from drowning, following a seizure in a bath at a unit run by Southern Health NHS Trust in 2013. He was just 18 years old. The Trust pleaded guilty to breaching health and safety law and his death led to the discovery of other unexplained deaths. She considered the inquest in a blog: https://mydaftlife.com/2018/04/20/danny-tozer/ and explained that “Learning disability is a kind of ‘get out of jail’ natural cause of death card.” She pointed to the concentration by Mencap on the trauma of the staff, without any attention being paid to the trauma of the residents. She pointed to the cross-examination of the Tozers on the first day of the inquest: “Did they complain? Did they complain enough? Why didn’t they make their concerns more apparent? Why and why not? Hints of ‘difficult parents’ dripped into evidence.”

She ended by saying that there was a clear sense from Danny’s inquest, that if someone with epilepsy has learning difficulties, it doesn’t really matter if they died. This was “an incomprehensible position sustained after both Danny, LB (and others) died. I don’t have words for this. Just tears.”

After the verdict Simon Wigglesworth, deputy chief executive of Epilepsy Action, said: “We were very sad to learn of Danny’s story and the unimaginable grief his family is going through after his death.”

He added: “This is a tragic case which highlights the need for consistent and co-ordinated care for people with complex epilepsy and learning disabilities. One in five people with epilepsy also have learning disabilities. The more severe the learning disability the higher the possibility that the person will also have epilepsy.” He highlighted the need for more research.

The only way for the family to have challenged the Coroner’s verdict would have been an expensive judicial review within three months but at the time they had neither the emotional energy or other resources to do so and they had lost faith in a legal system that they felt had failed them.

Mencap’s undisclosed review

Edel Harris took over as chief executive of Mencap in January 2020. She met with Danny’s parents on Zoom in November 2020 after they wrote to her expressing their distress following reports of further issues at the home. She wrote to them afterwards, explaining that she could not comment on previous events within Mencap, but acknowledged that “Mencap let you down. There were several points where we could have done things better.” But there was more. Harris told the family, to their surprise, that Mencap had undertaken a serious case review in the autumn of 2017, which had been commissioned by the charity’s trustees.

The review was not disclosed to the inquest. The Tozers were never invited to contribute to it. In September 2017 the organisation organised a lessons learned workshop, attended by executive team members and managers. The findings of the review were reported to the board of trustees in October 2017.

Harris shared the review with the family and said “I apologise that all of this wasn’t shared with you sooner”.

The review says: “we have decided not to contact the family as part of this review”, justifying this as a way of avoiding adding to their grief. The Mencap internal review acknowledged that Danny’s plan was deviated from on the day he died, with Danny not checked on from up to 25 minutes. It further noted that there was no “shared understanding of the level of supervision required to support the management of his epilepsy” and that at times the staff were perceived by the family to be ‘dismissive of their concerns’.

In a follow up letter to the CEO, the Tozers wrote: “We appreciate that you have made clear that you would not have agreed with how this was handled, but can you explain why this did not happen or why [the independent reviewer]’s statement to the court that she was surprised that Mencap had not done an internal inquiry ‘and continued to be so’ was not corrected?…It rather undermines Mencap’s barrister’s statement at the first PIR that Mencap wished to be ‘transparent”.

The additional trauma from a lack of accountability and transparency

The Tozers are at pains to stress that there were many incidents of good practice at the house where Danny lived, and some staff members went out of their way to offer support. But they are left feeling that the system that should have cared for Danny let him down – and has left them with life-long trauma.

Noelle Blackman is the chief executive of Respond, which offers therapeutic support to disabled people and their families who have experienced trauma. Blackman has worked with the Tozers and other bereaved families. The Tozers gave the writer of this article permission to speak about Danny in this context with Noelle Blackman.

Blackman stresses the huge trauma of the system that people with disabilities and their families are caught up in from the get-go: “Families are so used to so much trauma coming from the system at them, that their threshold of awfulness is higher than most families.” When a family is then bereaved, she explains, it can take time for them to process not only the death, but what accompanies it – a lack of justice, accountability and transparency.

“Families have to catch up with themselves and process and recognise, this is outrageous, this should never have happened. It took a while for Rosie to realise this wasn’t OK.”

But a decision to challenge isn’t easy and it takes a huge toll on families, who are already grieving. “They have to go into a fight mode to challenge. The fight is so extreme, it is so hard to be heard, and to get things in motion and they are invariably let down. The fight…is never resolved.”

She points to the injustice that often makes it impossible for families to completely recover. “A death like this can never become bearable..the families I have supported, the wound of it is so large..that it is triggered at the slightest thing…there is almost never an acknowledgement that something went wrong, that somebody messed up…You feel quite helpless as a bereavement organisation; all you can do is be on that journey with the family and say it’s OK.”

But she ends by saying, that the one “wonderful” thing that came out of the group bereavement counselling was that the families could “come together, share together and they got to a point where they could talk about the wonderfulness of the young people they had lost.”

City of York Council and Mencap were contacted and given a right to reply for this article. The council did not respond to two emails giving it a right to reply.

A Mencap spokesperson said:

“Our CEO, Edel Harris met Mr and Mrs Tozer and discussed many of the questions you have raised. We have taken time as an organisation to reflect on this tragedy … We respect the fact that Danny’s anniversary is a difficult time for Mr and Mrs Tozer. Our teams will join everyone who knew and loved Danny in remembering him on 22nd September.”

The Tozer family are left with memories. Danny loved life, he loved Motown music, as well as playing his own electric piano and hearing percussion. Rosie remembers, “When he was little he would sing his favourite songs with perfect pitch until his speech diminished. Some people really got him. I remember my mum’s birthday was in a community hall with a piano, and we went down to Oxfordshire to it, and he played away on the piano, just doing his own thing.”

Rowena, Danny’s sister, says simply: “I miss our family unit, the five of us. We navigated the world together. I miss the potential alternative of us being together. My daughters would have loved him, and he would have loved them too. That future isn’t happening now.”

Tim remembers his zest for life, and one particular ferry trip to Amsterdam that seemed to sum up something essential about the young man that has been lost and is still loved. “Danny had got into his pyjamas to go to bed, and all of a sudden he leaps up, rushes down all these flights of stairs and I follow him in my pyjamas and we end up on the dance floor, and there he is, in the middle, dancing disco. That’s the kind of guy he was.”

If you have any information that could help to better understand the circumstances of Danny Tozer’s death, you can contact us confidentially through Facebook or Twitter @DyingToMatter